With the spacecraft out of contact, it will be Friday before mission operators confirm its historic flyby.

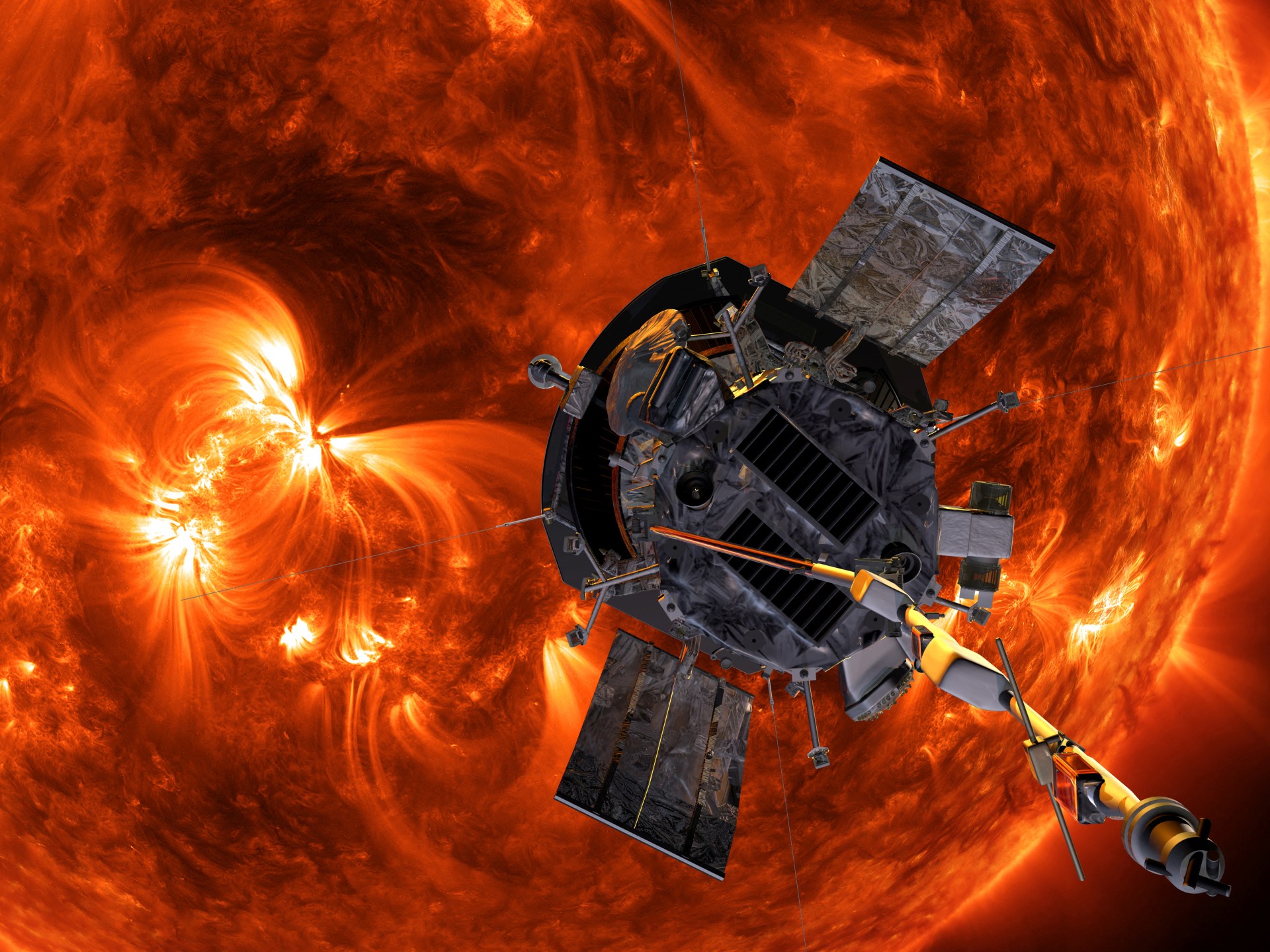

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is expected to make history by flying into the sun’s outer atmosphere, called the corona, on a mission to help scientists learn more about Earth’s closest star.

“No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star, so Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory,” Nick Pinkine, mission operations manager at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, said in a United States space agency blog on Tuesday.

Parker was on course to fly 6.1 million kilometres (3.8 million miles) from the sun’s surface at 11:53 GMT on Tuesday. With the spacecraft out of contact, it will be Friday before mission operators confirm its health after the close flyby.

Moving at up to 692,000km/h (430,000mph), fast enough to fly from Washington, DC, to Tokyo in under a minute, the spacecraft will endure temperatures of up to 982 degrees Celsius (1,800 degrees Fahrenheit), NASA said on its website.

If the distance between Earth and the sun were the equivalent of the length of a 100-yard (91.4-metre) American football field, the spacecraft should have been about 4 metres (4.4 yards) from the end zone at the moment of its closest approach – known as the perihelion.

When the probe first passed into the solar atmosphere in 2021, it found new details about the boundaries of the sun’s atmosphere and collected close-up images of coronal streamers, cusp-like structures seen during solar eclipses.

Since the spacecraft launched in 2018, the probe has been gradually circling closer towards the sun, using flybys of Venus to gravitationally pull it into a tighter orbit with our solar system’s star.

One instrument on board the spacecraft captured visible light from Venus, giving scientists a new way to see through the planet’s thick clouds to the surface below, NASA said.

By venturing into these extreme conditions, Parker has been helping scientists tackle some of the sun’s biggest mysteries: how solar wind originates, why the corona is hotter than the surface below and how coronal mass ejections – massive clouds of plasma that hurl through space – are formed.

Tuesday’s flyby is the first of three record-setting close passes with the next two – on March 22 and June 19 – expected to bring the probe back to a similarly close distance from the sun.

Leave a Reply