Rich countries have pledged to contribute $300bn a year by 2035 to help poorer nations combat the effects of climate change after two weeks of intense negotiations at the United Nations climate summit (COP29) in Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku.

While this marks a significant increase from the previous $100bn pledge, the deal has been sharply criticised by developing nations as woefully insufficient to address the scale of the climate crisis.

This year’s summit, hosted by the oil and gas-rich former Soviet republic, unfolded against the backdrop of a looming political shift in the United States as a climate-sceptic Donald Trump administration takes office in January. Faced with this uncertainty, many countries deemed the failure to secure a new financial agreement in Baku an unacceptable risk.

Here are the key takeaways from this year’s summit:

‘No real money on the table’: $300bn climate finance fund slammed

While a broader target of $1.3 trillion annually by 2035 was adopted, only $300bn annually was designated for grants and low-interest loans from developed nations to aid the developing world in transitioning to low-carbon economies and preparing for climate change effects.

Under the deal, the majority of the funding is expected to come from private investment and alternative sources, such as proposed levies on fossil fuels and frequent flyers – which remain under discussion.

“The rich world staged a great escape in Baku,” said Mohamed Adow, the Kenyan director of Power Shift Africa, a think tank.

“With no real money on the table, and vague and unaccountable promises of funds to be mobilised, they are trying to shirk their climate finance obligations,” he added, explaining that “poor countries needed to see clear, grant-based, climate finance” which “was sorely lacking”.

The deal states that developed nations would be “taking the lead” in providing the $300bn – implying that others could join.

The US and the European Union want newly wealthy emerging economies like China – currently the world’s largest emitter – to chip in. But the deal only “encourages” emerging economies to make voluntary contributions.

Failure to explicitly repeat the call for a transition away from fossil fuels

A call to “transition away” from coal, oil, and gas made during last year’s COP28 summit in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, was touted as groundbreaking – the first time that 200 countries, including top oil and gas producers like Saudi Arabia and the US, acknowledged the need to phase down fossil fuels. But the latest talks only referred to the Dubai deal, without explicitly repeating the call for a transition away from fossil fuels.

Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev referred to fossil fuel resources as a “gift from God” during his keynote opening speech.

New carbon credit trading rules approved

New rules allowing wealthy, high-emission countries to buy carbon-cutting “offsets” from developing nations were approved this week.

The initiative, known as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, establishes frameworks for both direct country-to-country carbon trading and a UN-regulated marketplace.

Proponents believe this could channel vital investment into developing nations, where many carbon credits are generated through activities like reforestation, protecting carbon sinks, and transitioning to clean energy.

However, critics warn that without strict safeguards, these systems could be exploited to greenwash climate targets, allowing leading polluters to delay meaningful emissions reductions. The unregulated carbon market has previously faced scandals, raising concerns about the effectiveness and integrity of these credits.

Disagreements within the developing world

The negotiations were also the scene of disagreements within the developing world.

The Least Developed Countries (LDCs) bloc had asked that it receive $220bn per year, while the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) wanted $39bn – demands that were opposed by other developing nations.

The figures did not appear in the final deal. Instead, it calls for tripling other public funds they receive by 2030.

The next COP, in Brazil in 2025, is expected to issue a report on how to boost climate finance for these countries.

Who said what?

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen hailed the deal in Baku as marking “a new era for climate cooperation and finance”.

She said the $300bn agreement after marathon talks “will drive investments in the clean transition, bringing down emissions and building resilience to climate change”.

US President Joe Biden cast the agreement reached in Baku as a “historic outcome”, while EU climate envoy Wopke Hoekstra said it would be remembered as “the start of a new era for climate finance”.

But others fully disagreed. India, a vociferous critic of rich countries’ stance in climate negotiations, called it “a paltry sum”.

“This document is little more than an optical illusion,” India’s delegate Chandni Raina said.

Sierra Leone’s Environment Minister Jiwoh Abdulai said the deal showed a “lack of goodwill” from rich countries to stand by the world’s poorest as they confront rising seas and harsher droughts. Nigeria’s envoy Nkiruka Maduekwe called it “an insult”.

Is the COP process in doubt?

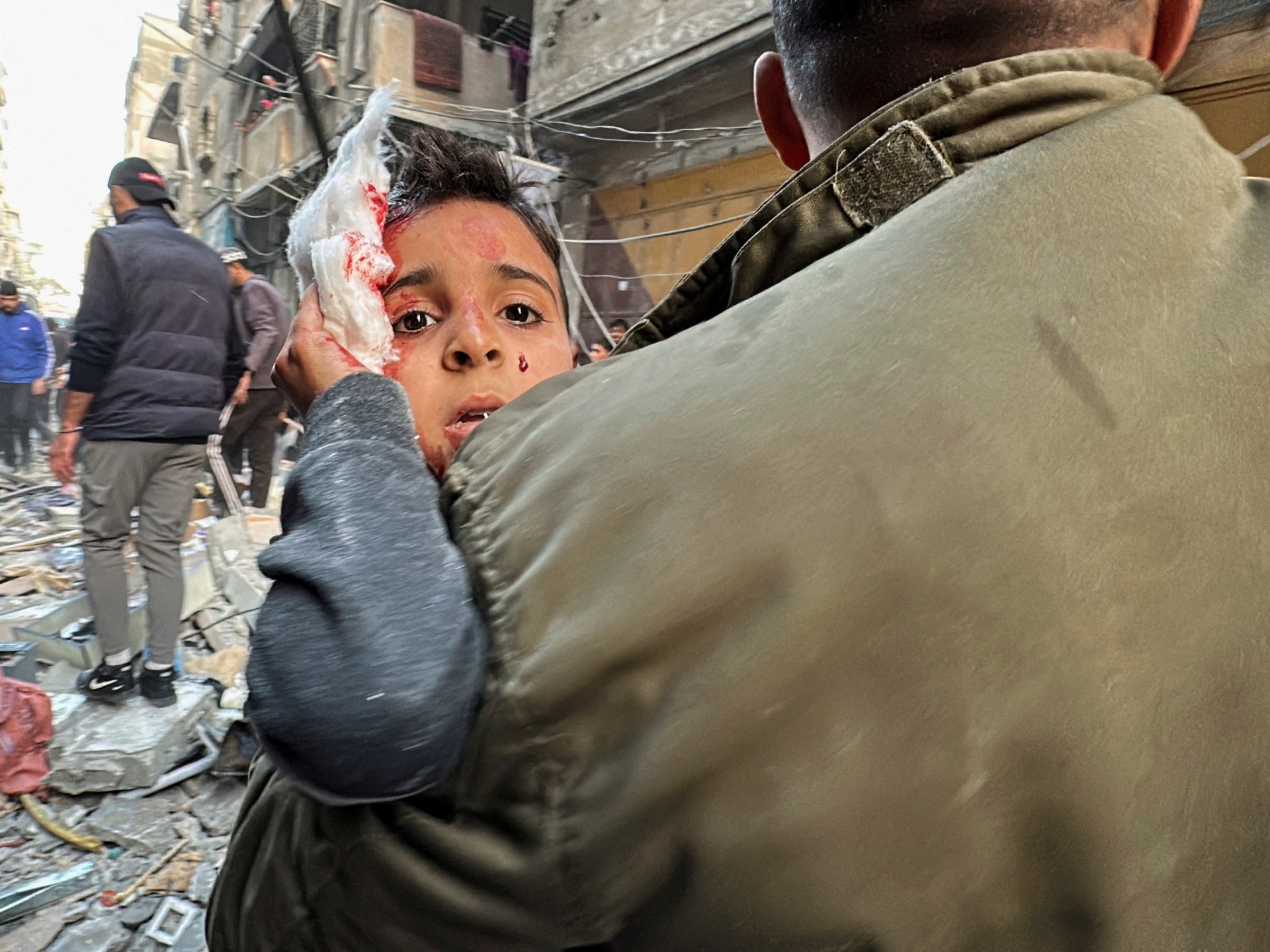

Despite years of celebrated climate agreements, greenhouse gas emissions and global temperatures continue to rise, with 2024 on track to be the hottest year recorded. The intensifying effects of extreme weather highlight the insufficient pace of action to avert a full-blown climate crisis.

The COP29 finance deal has drawn criticism as inadequate.

Adding to the unease, Trump’s presidential election victory loomed over the talks, with his pledges to withdraw the US from global climate efforts and appoint a climate sceptic as energy secretary further dampening optimism.

‘No longer fit for purpose’

The Kick the Big Polluters Out (KBPO) coalition of NGOs analysed accreditations at the summit, calculating that more than 1,700 people linked to fossil fuel interests attended.

A group of leading climate activists and scientists, including former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, warned earlier this month that the COP process was “no longer fit for purpose”.

They urged smaller, more frequent meetings, strict criteria for host countries and rules to ensure companies showed clear climate commitments before being allowed to send lobbyists to the talks.

Leave a Reply